No, not because of Fukushima: An Explanation of Northern California’s Red Abalone Decline

By Malina Loeher

“Oh, because of Fukushima…” When beachgoers see my abalone shirt and ask about my conservation work, this is the misconception frequently returned to me in northern California. Coastal residents have been harvesting red abalone for hundreds of years, but recent population decline and closure of the last recreational fishery have brought abalone into the public’s eye.

Often I hear, “it’s because of the urchins!” or “climate change, am I right?”

The common thread between all of these statements is the amount of information they leave out. It’s not any one thing keeping abalone from reproducing, growing, and reestablishing populations. It’s the onslaught of several stressors all at once.

Red abalone, inhabiting coastline from Southern Oregon to Baja California, are the largest abalone species in the world, with robust shells and a strong, meaty foot. They can fast for weeks at a time, withstand competition for food, and tolerate variable ocean temperatures. But in known history, red abalone in Northern California have never simultaneously defended against prolonged lack of kelp, increased competition via urchins, and warmed waters for many consecutive seasons.

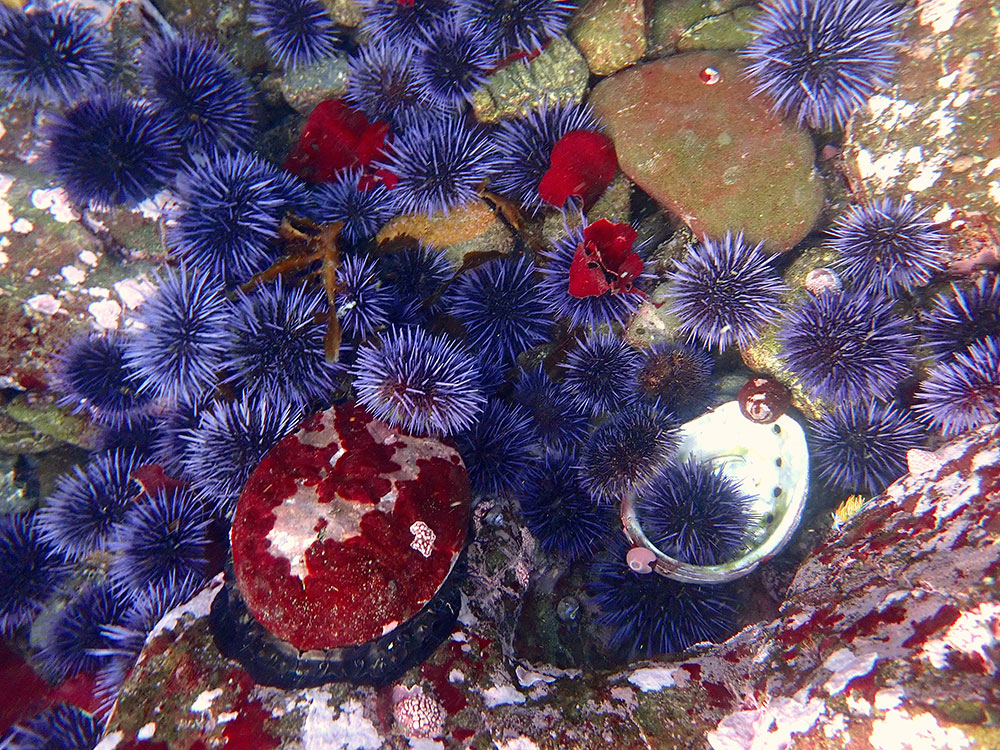

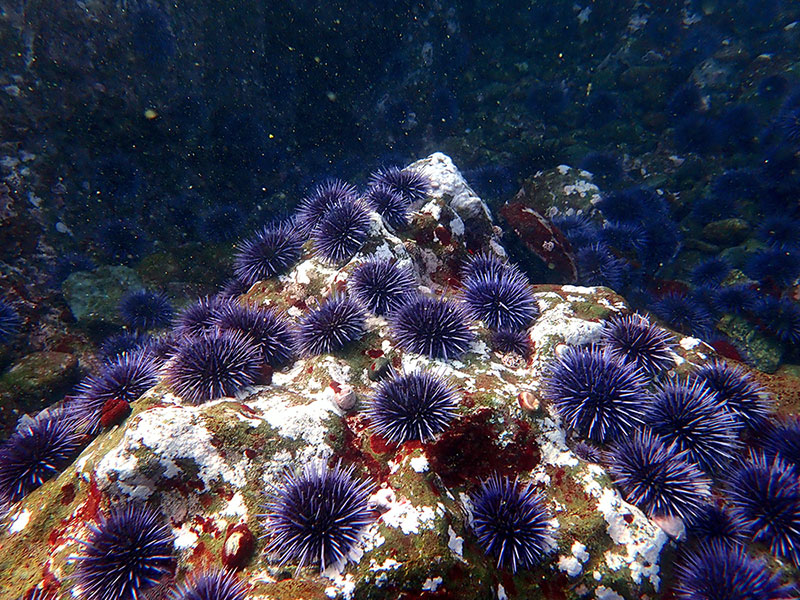

Kelp forests are both home and food for abalone. When kelp is lush, its primary production supports a plethora of marine species ranging from the tiniest of crab larvae all the way up to roving pods of orcas. Grazers like abalone and urchins joust, at a snail’s pace, for their seaweedy meals. Unfortunately for the red abalone, its purple urchin rival is fierce, and their common resource is limited. Usually, rowdy urchins are kept in check by equally gluttonous, predatory sea stars, but 2013-2015 saw a wasting disease sweep through North American sea stars, critically upsetting the balance of grazing species. Urchins are hardy, fast, and voracious, and can persist without food far longer than a soft-bodied abalone.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation describes a semi-regular collection of temperature shifts, accompanying winds, and ocean currents across the Pacific Ocean, which can impact everything from weather to abalone snacks. Usually, shifts in air and water temperatures force California coastal surface waters to be displaced by cold, nutrient-rich water from the ocean depths (this is called ‘upwelling’). These water inversions fertilize giant seaweeds, like the golden Macrocystis canopies celebrated by divers, and the ropy Postelsia stalks trampled by intertidal explorers. However, in El Niño years, like 2015-2016, California waters are warmer, upwelling is weak or nonexistent, and nutrients fail to reach kelp, meaning less food for uncomfortably warm abalone.

This is the current status of red abalone in Northern California: unable to escape from chronically warmed waters, with little available food, no signs of kelp bed recovery, and stuck with a highly populous competitor that beats them to the snack bar every time.

It could be years before a sustainable abalone fishery returns. But if even one of these circumstances change, perhaps they will recover for the centuries to come.

(As for the 2011 event in Fukushima, Japan, its radiation never discernibly impacted California.)

Sources and additional info:

- The ‘Perfect Storm’

- El Niño Southern Oscillation

- Red Abalone Fishery Management Plan

- Sea Star Wasting Disease (MARINe)

- WHOI FAQ’s on Fukushima

More from Malina: